July 2025 Director's Journal

“It’s not easy to think in reverse,” Ebenezer Galluzzo coaches, introducing us to the cyanotype process at the start of his Environmental Portraits workshop.

On the surface, he’s talking about technique—how light exposes what isn’t covered, how images emerge from absence. But as the morning fog lifts, his through-the-looking-glass invitation hovers over my work table like a caterpillar’s riddle: Who are you? Who are you not? Curiouser and curiouser.

I’m here with my parents. Or maybe—thinking in reverse—they’re here with me. As a child, I grew up inside the creative ethos and rhythms of the schools they led—the kind of schools where reading and drawing for pleasure are celebrated, and where unstructured time for play is part of every day.

Having them here with me at Sitka feels like a rare opportunity to collaborate again. What will we make together?

“Aesthetically, they’re wonderful. They look great,” shares longtime Sitka friend Laura Doyle, scrutinizing her test prints from the day before—made with invasive plants—and taking us inside her overnight moral dilemma. “For me, making pieces about my relationship with this environment… I’ve spent so much time weeding invasives. I decided that today, I can’t use them.”

Her work space is now strewn with native lady ferns and elderberries. There’s a lightness to her now, a playfulness. Something has clicked into place—like the door of a vault, unlocked, ready to be pulled open.

We’re no longer just making pretty blue and white prints of ferns and flowers. It’s about what we choose to include—and what we’re ready to leave out, or change.

“As humans, we tend to separate things into this or that—native or invasive, belonging or other,” Ebenezer reflects, speaking to the hard lines we draw around what counts as natural and beautiful—and the pressure to edit ourselves to conform. “We do this to people, to ourselves,” he continues. “But how am I in true relationship with myself, with others, with these plants, with nature? How am I part of nature?”

Despite his caution around polarizing opposites, Ebenezer’s deeper wisdom reminds me of a favorite quote from Brazilian educational philosopher Paulo Freire:

“There is no such thing as neutral education. Education either functions as an instrument to bring about conformity or freedom.”

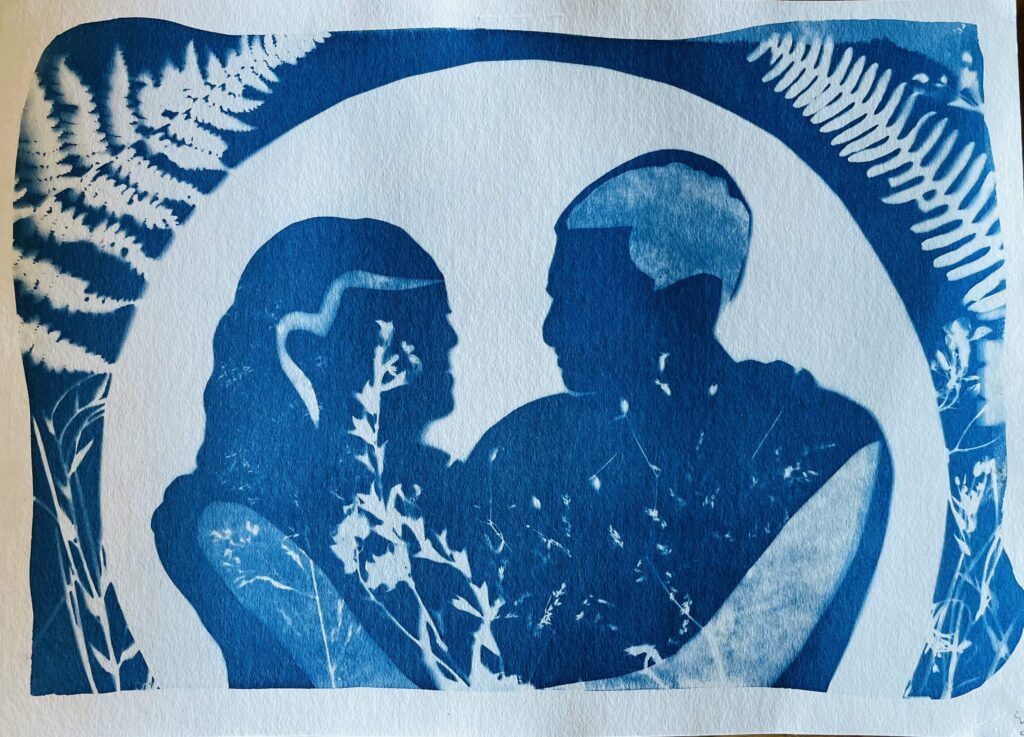

“For me, this is the ’80s,” my dad shares on day three during our final group reflection, gesturing toward the mommy-daddy-daughter cyanotype triptych we’ve spent the last day making together. “This is emotional for me—for us to get to do this again. To collaborate with Alison.”

I brush the beginnings of a tear away before it can form, throat tight.

Maybe that’s what thinking in reverse really offers. Not a nostalgic return, but a way to see where we’ve come from more clearly—so we can choose what to carry forward.

On the final afternoon, we experiment with gold leaf to adorn elements from our test prints and portraits—marking the moments we want to celebrate.

“I’m not a ‘put a bird on it’ artist,” Ebenezer confesses with a smile. “I’m a put a halo on it artist.”

“When I prepped this paper, I painted all the way to the edges instead of leaving a border,” my mother shares during our closing circle. “When I clipped the glass on top, I accidentally printed the binder clips—so I chose to adorn my mistake.”

My folks—as parents and as educators—have always believed in learning by doing, in giving children time and space to explore and create. Opportunities for this kind of lifelong learning feel rarer today, worth gilding.

As one participant shared on the first morning, “I come to Sitka to drink coffee and make art together with people.”

Whether you take a workshop at Sitka with friends or family, or to connect with kindred spirits you’ve yet to meet, I hope you find a sense of creative belonging and homecoming here.

A sense of freedom.

Alison

Portrait of my parents (below). Thank you, Mama, Papa—and Ebenezer—for three golden days I’ll always remember, with a halo around them.

- Journals